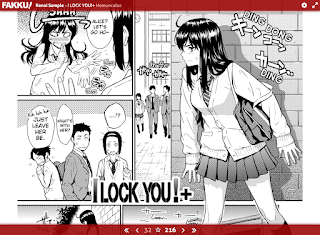

On the newly legal 'hentai' erotic, pornographic manga/anime site, FAKKU, for The Japan Times

By ROLAND KELTS

When Jacob Grady began pirating anime and manga online eight years ago, he was still in college. He took out student loans to pay the server bills, and figured that if he ever made enough money from the site to purchase a round-trip flight to Japan, the effort and expense would be worth it.

Like many Americans, he got hooked on Japanese pop culture as a kid through the Cartoon Network’s action-oriented programming block called “Toonami” (“cartoon tsunami”). He would race home from school to catch the latest episodes of “Dragonball Z” and “Gundam Wing.”

But Grady was not pirating anime adventure series or kids’ shows like “Pokemon.” The content on his site was what most non-Japanese call “hentai” (abnormal, perverted), and in Japan is still largely known as ero-manga, ero-anime, or just porno.

“At some point, going through puberty and exploring the Internet for the first time, I came across hentai,” he says. “I just never looked back.”

Outside of Japan, hentai now refers to an entire subgenre of anime and manga that features highly stylized eroticism, with characters whose sexual organs often defy the norms of physics, and whose behavior and physical contortions belie any semblance of realism.

For some, hentai is a testament to the immense creativity of Japanese manga and anime artists, the modern version of Japanese shunga — sexually explicit scrolls dating back to the Heian Period (794-1185), when Japanese artists were influenced by Chinese erotica, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints flourishing in the Edo Period (1603-1868). But for others, hentai is depraved, a sign of Japan’s lax public and religious morality, and the nation’s failure to adapt to modern norms of femininity and civility.

The hentai debate is not innocuous. In 2009, former U.S. Marine Christopher Handley was sentenced to six months in an Iowa prison for ordering ero-manga by mail from Japan. In 2011, an American had his laptop, iPad and iPhone seized at the Canadian border, where officials deemed his anime and manga images “obscene” and “child pornography.”

Ex-Tokyo Gov. Shinto Ishihara made one of his last stands an attempt to outlaw what he called “manga and anime disrupting the social order.” His bill was branded “the nonexistent youth legislation.” As vague as he was hypocritical, Ishihara caused a firestorm: Manga and anime artists and producers abandoned the Tokyo Anime Fair (which he chaired) and staged public protests. Municipal officials argued — some for the protection of children, others against Ishihara’s double standard as a former novelist and playwright of many risque stories.

Eventually, the Japanese government outlawed the possession of live-action child pornography — in which actual human beings are exploited — but left manga and anime, works of the imagination that do not involve the coercion or slavery of people, alone.

Grady is determined to bolster the cause of artistic freedom over reflexive censorship: “We will never back down from publishing controversial content.”

His strategy is working. These days, round-trip tickets to Tokyo are frequent and unremarkable. Grady’s site, Fakku.net (yes, “fakku”), gets over 1 billion page views per month, and over 10 million unique clicks, making it one of the top 50 adult websites in the world. Twelve full-time employees now manage the site from their office in Portland, Oregon.

And Grady is forging ahead with partnerships. Japanese publishers of the two biggest hentai magazines in Japan, Comic Kairakuten and Comic X-Eros, have agreed to simultaneously publish with Fakku in the U.S. — meaning that the print versions will appear in America on the same day they hit convenience-store magazine racks in Japan.

But these partnerships can’t happen without legitimacy. No surprise, then, that Grady is preparing Fakku to go legal at the end of 2015 — following in the hallowed footprints of Crunchyroll.com, the once-pirate anime and manga site that is now a multimillion-dollar enterprise, owned by Hollywood’s Chernin Group.

He knows that the transition from free to paid hentai will be rough. “I expect traffic to drop significantly once we make the full transition to a legit website with entirely licensed content,” he tells me. “But the remaining user base will still be substantial, and made up entirely of people who are supportive of what we’re doing and supportive of the industry at large. We’ve sold over 50,000 books through our website in the first year.”

Grady’s move into co-licensed publishing, and licensed online content, is a first in hentai deliverables. Recently, he also sealed a partnership with veteran artist Toshio Maeda, creator of the porn classic “La Blue Girl.” The two appeared together at Anime Expo in Los Angeles in July and are about to announce a crowdfunding project this fall.

On the verge of going legit, with paid subscribers and premium content, Grady is sanguine about his future and devoted to quality. Hentai is not just porn, he insists. In Southern California, the hotbed of live-action porn, you can get any “stud” or “babe” to perform in front of a camera. But you can’t draw hentai if you’re not an artist — or, some say, if you’re not Japanese.

“Hentai is art, and as art it can explore all kinds of themes and worlds that live-action porn never could,” Grady says. “But more importantly, I feel like hentai tends to have plot and story that you can follow and get invested in. I’ve read stories that have made me emotional, happy or sad. And seeing some of the comments on Fakku, I know the community feels those emotions as well.”

Roland Kelts is the author of “Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture has Invaded the U.S.” He is a visiting scholar at Keio University in Tokyo.