The future of anime? LeSean Thomas' "Cannon Busters"

'Cannon Busters': Bending anime rules in all the right ways

The Japan Times

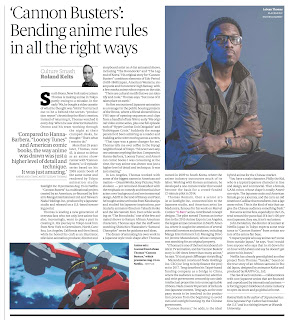

South Bronx, New York native LeSean Thomas is making anime in Tokyo partly owing to a mistake.

In the early ’90s he bought a video cassette of what he thought was “Akira” but turned out to be a behind-the-scenes “production report” documenting the film’s creation. Instead of returning it, Thomas watched it every day. When he saw director Katsuhiro Otomo and his team working through the night at their cramped desks, he thought: That’s what I want to do.

More than 20 years later, Thomas, now 43, has become an anime showrunner with “Cannon Busters,” a 12-episode series based on his 2005 comic book of the same name and rendered by Tokyo animation studio Satelight Inc. The multinational project was created by an American, co-financed by Britain’s Manga Entertainment Ltd. and Taiwan’s Nada Holdings Inc., produced by a Japanese studio and released on major U.S. and Chinese streaming portals, Netflix and Bilibili.

Thomas is leading a new generation of overseas fans who not only love anime but also, increasingly, want to play a part in creating it. His journey to Tokyo took him from New York to Los Angeles and Seoul, while he honed his craft as an illustrator and animation director, producer and storyboard artist on A-list animated shows “The Boondocks” and “The Legend of Korra.”

His original story for “Cannon Busters” combines elements of Edo Period (1603-1868) Japan, American Westerns, steampunk and Eurocentric high fantasy, with a few mecha anime robot tropes on the side.

“There are cultural motifs that we can identify and racially code,” Thomas tells me over coffee in the Yoyogi neighborhood of Tokyo, “but none of it takes place on earth.”

Lead character S.A.M. from "Cannon Busters" (Netflix)

He first encountered Japanese animation as a teenager in the public housing projects of the Bronx, where a friend showed him a VHS tape of opening sequences and clips from a handful of late ’80s to early ’90s original video anime series. Suddenly the manga panels he’d been admiring as a reader and budding artist were moving across a screen.

“That tape was a game changer for me,” he says. “I’d never seen anyone animate anything like that. Compared to Hanna-Barbera, ‘Looney Tunes,’ and American comic books I was consuming at the time, the way anime was drawn was just a higher level of detail and technique. It was just amazing.”

In Los Angeles, Thomas worked with some of the biggest names in American animation — DreamWorks, Sony Pictures, Nickelodeon — yet remained dissatisfied with their emphasis on comedy and theatrical characters over background and environmental design.

.jpg)