My review of YASUKE: Black culture meets Japanese history in an anime first

African samurai earns hero status in new anime ‘Yasuke’

Of the record-high 40 original anime programs Netflix is launching this year, none may be better pedigreed or more timely than “Yasuke,” a six-episode series about Japan’s only known Black samurai.

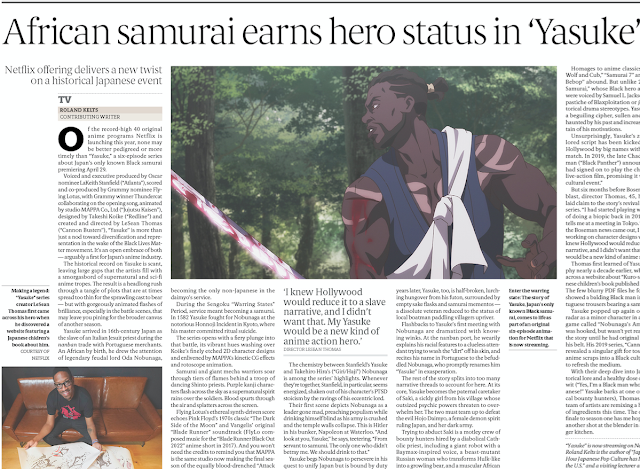

Voiced and executive produced by Oscar nominee LaKeith Stanfield (“Atlanta”), scored and co-produced by Grammy nominee Flying Lotus, with Grammy winner Thundercat collaborating on the opening song, animated by studio MAPPA Co., Ltd (“Jujutsu Kaisen”), designed by Takeshi Koike (“Redline”) and created and directed by LeSean Thomas (“Cannon Busters”), “Yasuke” is more than just a nod toward diversification and representation in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s an open embrace of both — arguably a first for Japan’s anime industry.

The historical record on Yasuke is scant, leaving large gaps that the artists fill with a smorgasbord of supernatural and sci-fi anime tropes. The result is a headlong rush through a tangle of plots spread too thin at times for the sprawling cast to bear — but with gorgeously animated flashes of brilliance, especially in the battle scenes, that may leave you pining for the broader canvas of another season.

Yasuke arrived in 16th-century Japan as the slave of an Italian Jesuit priest during the nanban trade with Portuguese merchants. An African by birth, he drew the attention of legendary feudal lord Oda Nobunaga, becoming the only non-Japanese in the daimyo’s service.

During the Sengoku “Warring States” Period, service meant becoming a samurai. In 1582 Yasuke fought for Nobunaga at the notorious Honnoji Incident in Kyoto, where his master committed ritual suicide.

The series opens with a fiery plunge into that battle, its vibrant hues washing over Koike’s finely etched 2D character designs and enlivened by MAPPA’s kinetic CG effects and rotoscope animation.

Samurai and giant mecha warriors soar through tiers of flames behind a troop of dancing Shinto priests. Purple kanji characters flash across the sky as a supernatural spirit rains over the soldiers. Blood spurts through the air and splatters across the screen.

Flying Lotus’s ethereal synth-driven score echoes Pink Floyd’s 1970s classic “The Dark Side of the Moon” and Vangelis’ original “Blade Runner” soundtrack (FlyLo composed music for the “Blade Runner Black Out 2022” anime short in 2017). And you won’t need the credits to remind you that MAPPA is the same studio now making the final season of the equally blood-drenched “Attack on Titan.”

The chemistry between Stanfield’s Yasuke and Takehiro Hira’s (“Giri/Haji”) Nobunaga is among the series’ highlights. Whenever they’re together, Stanfield, in particular, seems energized, shaken out of his character’s PTSD stoicism by the ravings of his eccentric lord.

Their first scene depicts Nobunaga as a leader gone mad, preaching populism while drinking himself blind as his army is crushed and the temple walls collapse. This is Hitler in his bunker, Napoleon at Waterloo. “And look at you, Yasuke,” he says, teetering. “From servant to samurai. The only one who didn’t betray me. We should drink to that.”

Yasuke begs Nobunaga to persevere in his quest to unify Japan but is bound by duty to decapitate his lord on command. Twenty years later, Yasuke, too, is half-broken, lurching hungover from his futon, surrounded by empty sake flasks and samurai mementos — a dissolute veteran reduced to the status of local boatman paddling villagers upriver.

Flashbacks to Yasuke’s first meeting with Nobunaga are dramatized with knowing winks. At the nanban port, he wearily explains his racial features to a clueless attendant trying to wash the “dirt” off his skin, and recites his name in Portuguese to the befuddled Nobunaga, who promptly renames him “Yasuke” in exasperation.

The rest of the story splits into too many narrative threads to account for here. At its core, Yasuke becomes the paternal caretaker of Saki, a sickly girl from his village whose outsized psychic powers threaten to overwhelm her. The two must team up to defeat the evil Hojo Daimyo, a female demon spirit ruling Japan, and her dark army.

Trying to abduct Saki is a motley crew of bounty hunters hired by a diabolical Catholic priest, including a giant robot with a Baymax-inspired voice, a beast-mutant Russian woman who transforms Hulk-like into a growling bear, and a muscular African shaman.

Homages to anime classics like “Lone Wolf and Cub,” “Samurai 7” and “Cowboy Bebop” abound. But unlike 2007’s “Afro Samurai,” whose Black hero and sidekick were voiced by Samuel L. Jackson, this is no pastiche of Blaxploitation or jidaigeki historical drama stereotypes. Yasuke remains a beguiling cipher, sullen and wounded, haunted by his past and increasingly uncertain of his motivations.