Monkey & Murakami in Manila, in the Philippines Inquirer

Want to satisfy your Murakami and manga cravings?

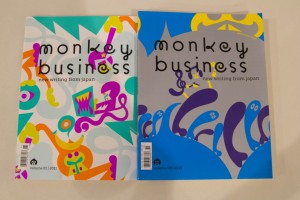

Check out Monkey Business

Japan Foundation, Manila hosts a forum on the new literary journal, with contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura talking about what makes Japanese literature and popular culture click

HARUKI Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto are familiar names in Japanese contemporary writing to Filipinos and the West, more familiar perhaps to the younger generations nowadays than, say, the modern writers such as Yukio Mishima, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, Kobo Abe, Shohei Ooka, Shusaku Endo and the Nobel laureates Yasunari Kawabata and Kenzaburo Oe.

Older lovers and readers of Japanese fiction and literature may say Filipinos should read the modern writers more (Ooka, for one, wrote the celebrated “Fires on the Plain,” about Japanese soldiers in the Visayas during the Second World War; and Endo, who wrote the novel “Silence,” which no less than Martin Scorsese himself is adapting into a movie, tackled overtly Catholic themes).

But even if younger Filipino readers are enamored of Murakami and Yamamoto, they may also be missing out on other writers in the Japanese contemporary writing scene who are just as qualified to land a best seller on various lists in the West as much as Murakami and the latest hit manga writer and illustrator.

A good way for Filipinos and Japanophiles to get acquainted with other Japanese writers and artists is through the new journal Monkey Business.

Japan Foundation, Manila hosted a forum last week to introduce to Manila the journal, which was represented by contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura.

Monkey Business is the only English-language annual of Japanese literature and popular culture in the world. It features different kinds of storytelling styles such as fiction, photography, graphic stories, haiku, tanka and essays.

The magazine selects only the best contemporary writing in Japan, said Kelts. It is edited by Motoyuki Shibata, a professor who is considered Japan’s best translator of American fiction into Japanese.

Among the magazine’s notable contributors are Murakami and Yoko Ogawa.

Japanese writers that have been published in Monkey Business include Aoko Matsuda, Mieko Kawakami, Masatsugu Ono, Mina Ishikawa, Masayo Koike and Yoko Hayasuke.

Exhilarating experience

During the talk “Monkey Business: New Japanese Writing” on Oct. 21 at Ayala Museum, Kelts, a Japanese-American, said he found helping edit and publish Monkey Business an exhilarating experience.

“We hope that through our experiences, we can help other artists and publishers around the world reach a global audience as well,” he said.

Kelts said there were three important lessons he learned in Monkey Business: Publish what you love; get excellent translators; and network with people all over the world.

“I should tell you that we only publish what we love,” Kelts said. “We don’t publish anything because the person is important or famous, and we don’t pretend that this is all of contemporary Japanese culture.”

He said Monkey Business was a hybrid publication with mixed contents from the East and West. Aside from Japanese writers, it has also published the works of Paul Auster, Charles Simic and Kelly Link.

Kelts said publishing the things you loved had a good chance of having people around the world liking your work.

“The translators have to be excellent writers, and they have to love the work that they are translating,” Kelts explained. “They have to live with the work because it is not just a job, it has to be a romance.”

Japanese imagination

Kitamura, who is known for his children’s books and comics, said the Japanese were naturally imaginative. They effortlessly knew how to break away from reality in creating their stories.

Kitamura and Kelts cited the works of animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. They also cited the fiction of Murakami and the famous animé “Pokemon.”

Kelts explained this imagination of the Japanese could be traced to Shintoism, a religion believing that even inanimate objects can have a spirit.

“In Japanese manga or animé, it can be from pure imagination, purely liberated from the biological world,” Kelts said. “There can be an animé of anything imaginable.”

Kelts mentioned that a popular animated series in Japan, Moyasimon, has some bacteria as its main characters. Kitamura added that he had works centered on a kettle and an overcoat.

Having released its initial volume in 2008, Monkey Business started as purely a journal in Japanese. Later, Shibata and co-editor Ted Goossen tapped Kelts to start the English version in 2010. Five issues in English have since been published.

Monkey Business is materialized through the Nippon Foundation and A Public Space, the magazine’s publisher based in Brooklyn, New York.

The talk was held under the auspices of the Japan Foundation Asia Center.

Visit MONKEY BUSINESS to purchase Monkey Business. Paperbacks and digital copies are available.

Check out Monkey Business

Japan Foundation, Manila hosts a forum on the new literary journal, with contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura talking about what makes Japanese literature and popular culture click

HARUKI Murakami and Banana Yoshimoto are familiar names in Japanese contemporary writing to Filipinos and the West, more familiar perhaps to the younger generations nowadays than, say, the modern writers such as Yukio Mishima, Jun’ichiro Tanizaki, Kobo Abe, Shohei Ooka, Shusaku Endo and the Nobel laureates Yasunari Kawabata and Kenzaburo Oe.

Older lovers and readers of Japanese fiction and literature may say Filipinos should read the modern writers more (Ooka, for one, wrote the celebrated “Fires on the Plain,” about Japanese soldiers in the Visayas during the Second World War; and Endo, who wrote the novel “Silence,” which no less than Martin Scorsese himself is adapting into a movie, tackled overtly Catholic themes).

But even if younger Filipino readers are enamored of Murakami and Yamamoto, they may also be missing out on other writers in the Japanese contemporary writing scene who are just as qualified to land a best seller on various lists in the West as much as Murakami and the latest hit manga writer and illustrator.

A good way for Filipinos and Japanophiles to get acquainted with other Japanese writers and artists is through the new journal Monkey Business.

Japan Foundation, Manila hosted a forum last week to introduce to Manila the journal, which was represented by contributing editor Roland Kelts and artist Satoshi Kitamura.

Monkey Business is the only English-language annual of Japanese literature and popular culture in the world. It features different kinds of storytelling styles such as fiction, photography, graphic stories, haiku, tanka and essays.

The magazine selects only the best contemporary writing in Japan, said Kelts. It is edited by Motoyuki Shibata, a professor who is considered Japan’s best translator of American fiction into Japanese.

Among the magazine’s notable contributors are Murakami and Yoko Ogawa.

Japanese writers that have been published in Monkey Business include Aoko Matsuda, Mieko Kawakami, Masatsugu Ono, Mina Ishikawa, Masayo Koike and Yoko Hayasuke.

Exhilarating experience

During the talk “Monkey Business: New Japanese Writing” on Oct. 21 at Ayala Museum, Kelts, a Japanese-American, said he found helping edit and publish Monkey Business an exhilarating experience.

“We hope that through our experiences, we can help other artists and publishers around the world reach a global audience as well,” he said.

Kelts said there were three important lessons he learned in Monkey Business: Publish what you love; get excellent translators; and network with people all over the world.

“I should tell you that we only publish what we love,” Kelts said. “We don’t publish anything because the person is important or famous, and we don’t pretend that this is all of contemporary Japanese culture.”

He said Monkey Business was a hybrid publication with mixed contents from the East and West. Aside from Japanese writers, it has also published the works of Paul Auster, Charles Simic and Kelly Link.

Kelts said publishing the things you loved had a good chance of having people around the world liking your work.

“The translators have to be excellent writers, and they have to love the work that they are translating,” Kelts explained. “They have to live with the work because it is not just a job, it has to be a romance.”

Japanese imagination

Kitamura, who is known for his children’s books and comics, said the Japanese were naturally imaginative. They effortlessly knew how to break away from reality in creating their stories.

Kitamura and Kelts cited the works of animator and filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki. They also cited the fiction of Murakami and the famous animé “Pokemon.”

Kelts explained this imagination of the Japanese could be traced to Shintoism, a religion believing that even inanimate objects can have a spirit.

“In Japanese manga or animé, it can be from pure imagination, purely liberated from the biological world,” Kelts said. “There can be an animé of anything imaginable.”

Kelts mentioned that a popular animated series in Japan, Moyasimon, has some bacteria as its main characters. Kitamura added that he had works centered on a kettle and an overcoat.

Having released its initial volume in 2008, Monkey Business started as purely a journal in Japanese. Later, Shibata and co-editor Ted Goossen tapped Kelts to start the English version in 2010. Five issues in English have since been published.

Monkey Business is materialized through the Nippon Foundation and A Public Space, the magazine’s publisher based in Brooklyn, New York.

The talk was held under the auspices of the Japan Foundation Asia Center.

Visit MONKEY BUSINESS to purchase Monkey Business. Paperbacks and digital copies are available.

.jpg)