My take on the year in anime for The Japan Times

So long, 2022. You've been quite the year for anime...

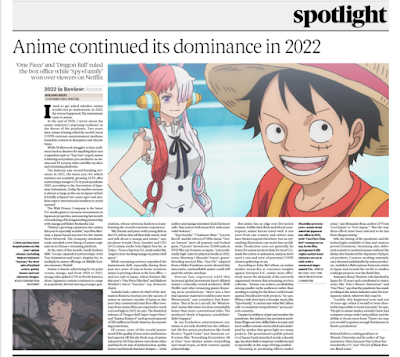

Anime continued its dominance in 2022

I used to get asked if anime would ever go mainstream. In 2022, the reverse happened: The mainstream came to anime.

At the end of 2020, I wrote about the anime industry’s surprising resilience in the throes of the pandemic. Two years later, anime is being called the world’s most COVID-resistant entertainment medium: bankable content in disruptive and chaotic times.

While Hollywood struggles to lure audiences back to theaters for anything that’s not a superhero epic or “Top Gun” sequel, anime is thriving everywhere you can find it: on cinema and TV screens, video and Blu-ray discs and streaming platforms.

The industry saw record-breaking revenues in 2021, the most recent year for which statistics are available, growing 13.3% after contracting a meager 3.5% in peak-pandemic 2020, according to the Association of Japanese Animations. Today the market overseas is almost as large as the one in Japan (which it briefly eclipsed two years ago) and analysts expect international numbers to trend upward.

The Walt Disney Company is the latest U.S. media giant to increase investments in Japanese properties, announcing last month a broadening of its longstanding partnership with manga publisher Kodansha Ltd.

“Disney’s growing expansion into anime this year is especially notable,” says Kim Morrissy, a Japan-based reporter for the Anime News Network. The company simultaneously unveiled a new lineup of anime originals on its Disney+ streaming platform.

At the start of this month, Saudi Arabia’s MBC Group expanded partnerships with Toei Animation and Sony’s Aniplex Inc. to multiply its anime offerings on Middle Eastern streamer, Shahid.

Anime is kinetic advertising for its print cousin, manga, and from 2020 to 2021, manga sales spiked 171% in North America alone. Japanese content continues to surge in popularity abroad among younger generations, whose ravenous fandom is transforming the overall consumer experience.

“My friends and peers with young kids in the U.S. tell me that all their kids watch, read and talk about is manga and anime,” says producer Joseph Chou, founder and CEO of CG anime studio Sola Digital Arts Inc. in Tokyo. “Even a big-box U.S. retail outlet like Target is now stocking manga on prime shelf space.”

While streaming services expedited the mainstream shift, especially during these past two years of stay-at-home isolation, anime is proving robust at the box office — and not only in Japan, where features like this year’s “One Piece Film Red” and Makoto Shinkai’s latest “Suzume” top domestic charts.

Tadashi Sudo, editor-in-chief of the Animation Business Journal, sees the success of anime in cinemas outside of Japan as this year’s key commercial trend. Box-office revenues from anime films are expected to reach a record high in 2022, he says. The theatrical releases of “Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero” and “Jujutsu Kaisen 0” each grossed upward of $30 million in North America, far exceeding projections.

Of course, none of this would matter much if the quality of new series and features had tapered off. But the fresh crop of anime released in 2022 has drawn raves from critics and fans for its mix of stylized action, quirky humor and kawaii character designs — what author and manga translator Zack Davisson calls “that action-with-heart feel, with some solid violence.”

“Spy×Family,” “Chainsaw Man,” “Lycoris Recoil” and the reboot of 1980s classic “Urusei Yatsura” were all popular and looked great. (“Lycoris” moved over 23,000 units in DVD/Blu-ray formats in Japan, “extraordinarily high” sales for physical media in 2022, notes Morrissy.) Masaaki Yuasa’s genre-blending musical film, “Inu-Oh,” adapted from a Hideo Furukawa novel, showed that innovative, unclassifiable anime could still push the artistic envelope.

Veteran fans expressed relief that increased global investment hasn’t diluted anime’s culturally rooted aesthetics. With Netflix and other streaming giants financing more productions, “there was a fear that Japanese material would become more Westernized,” says translator Dan Kanemitsu. “But as far as I can tell, the ‘Westernized’ anime titles have not done remarkably better than more conventional titles. The predicted ‘death of Japanese sensibilities’ didn’t happen.”

In our borderless entertainment era, anime is not only durable but also influential. Hit live-action productions like South Korea’s “Squid Game” and American sci-fi action film “Everything Everywhere All at Once” bear distinct anime storytelling and visual tropes, as their creators openly acknowledge.

But anime has an edge over live-action content. Unlike their flesh-and-blood counterparts, anime heroes travel well. A star actor from one country and culture may have limited appeal elsewhere, but an eye-catching illustration can excite fans worldwide. Production costs are generally far lower for anime projects than for most U.S.-made live action or animation, and you don’t need a cast and crew of potential COVID clusters gathering on set.

According to John McCallum, an anime market researcher at consumer insights agency Interpret LLC, anime more effectively meets the demands of the narrowly segmented viewers that streaming services cultivate. “Anime can achieve profitability among smaller niche audiences rather than needing to swing for the fences with broad-appeal, blockbuster-style projects,” he says. When a title does have a broader reach, like “Spy×Family,” it can become what McCallum calls “a consistent overperformer” across several countries.

Despite its ability to adapt and weather the pandemic, the industry has persistent problems: Wages are low, skilled labor is scant, and most staffers remain overworked and underpaid by studios that green-light too many projects. The government’s public-private Cool Japan Fund, launched nearly a decade ago, has done little to improve conditions and is reportedly on the verge of being scuttled.

“Investing in promising efforts makes sense,” says Benjamin Boas, author of “From ‘Cool Japan’ to ‘Your Japan.’” “But the way these efforts have been selected so far has been disappointing.”

Still, the timing of the pandemic and the technologies available to fans and creators proved fortuitous. Streaming sites delivered content to isolated masses without the delays that hindered the shipment of physical products. Creators working remotely, once deemed unthinkable by anime producers, enabled collaborations between artists in Japan and around the world so studios could get projects over the finish line.

Animator Henry Thurlow, who has lived in Japan for 13 years and contributed to major series like “JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure” and “One Piece,” says that the pandemic has made working in the anime industry easier for non-Japanese talent, wherever they may be.

“Luckily, this happened now and not 10 years ago, when it would’ve been absolutely impossible to work remotely,” he says. “People in anime studios wouldn’t have had computer setups with Cintiq tablets and the ability to Zoom every hour. There’s no way you would’ve gotten enough freelancers to finish a production.”

.jpg)